Molecular meth tests

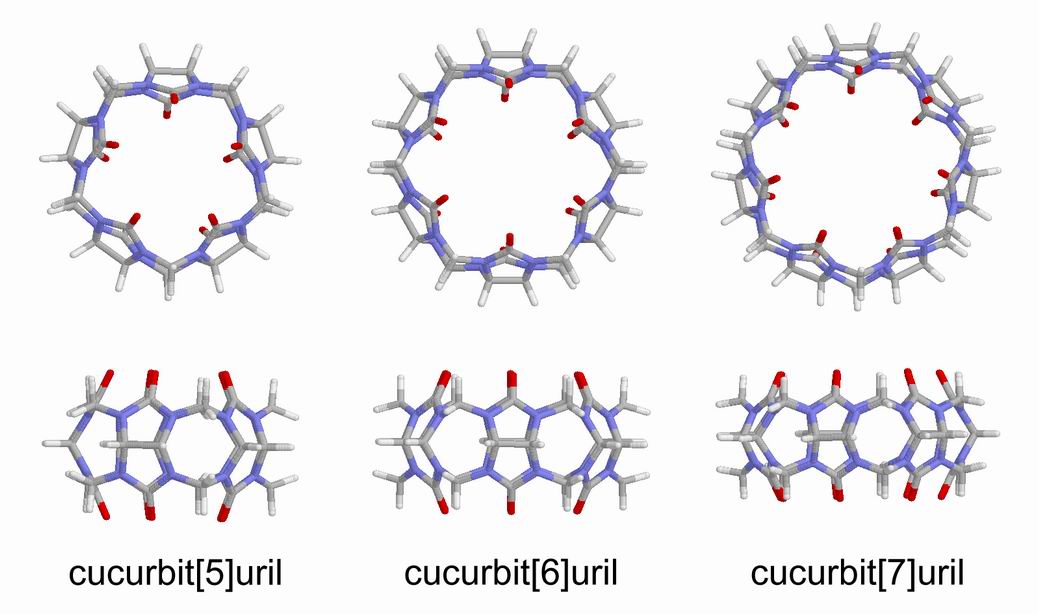

A few weeks ago, we reported on a micro monster truck race using vehicles made from cucurbiturils. Well, it turns out these wheel-shaped molecules are good for more than just racing.

This week, a different team from the Institute for Basic Science and Pohang University of Science and Technology, South Korea have used cucurbiturils to create drug sensors capable of detecting meth in as little as one drop of urine.

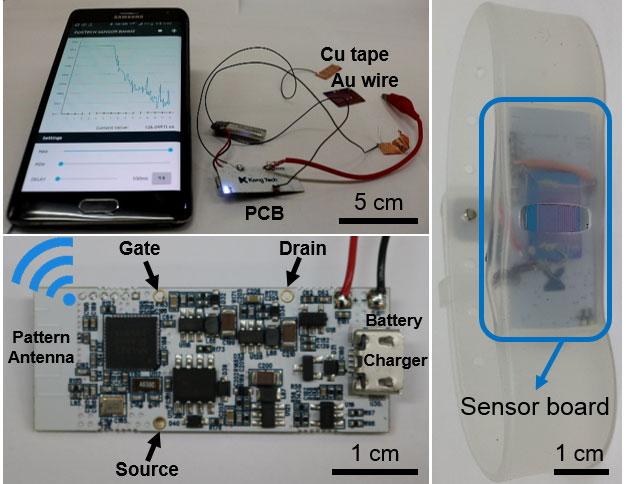

The hole in the middle of cucurbit[7]uril is the perfect fit for amphetamine drugs, and is now being used in an experimental sensor to detect the molecules in urine and other body fluids. It makes up part of an organic field-effect transistor, which generates an electrical signal when the drug is added. This sends a wireless message to an accompanying app via a Bluetooth antenna.

The team say that their new device can detect as little as 0.1 nanograms of amphetamine per millilitre of urine. Current tech can only pick up the drugs when they reach 10 nanograms per millilitre.

The kit is so small it can be worn on the wrist, offering the promise of a portable drugs test to rival an alcohol breathalyser. It's still a prototype though, and although it's working well in the lab, it's possible that other molecules present in urine could give a false positive.

The next step is to take the kit into clinical trials to find out whether it works in practice.

"Conventional drug detection generally use techniques that require long operation time, sophisticated experimental procedures, and expensive equipment with well-trained professional operators; moreover, they are not usually portable... Our method is a new type of drug sensor that can solve all these problems at once."

Joon Hak Oh, POSTECH

Dissolving food thermometers

Fresh produce looks set to join the ever-expanding Internet of Things as researchers at the Electronics Laboratory at ETH Zurich in Switzerland work on a soluble temperature sensor to keep tabs on food in transit.

Sign up to the T3 newsletter for smarter living straight to your inbox

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

The ultra-fine potato starch patch is thinner than a human hair, and contains an electrical filament made from a combination of biodegradable and biocompatible magnesium, silicone dioxide and nitride.

It can be folded, creased, stretched and submerged, and it lasts for at least two months before dissolving, so could be used to track fish and other groceries as they makes their way to supermarket shelves.

"Once the price of biosensors falls enough, they could be used virtually anywhere"

Giovanni Salvatore, ETH Zurich

The prototype currently has to be wired up to an external battery and a chip with a microprocessor and bluetooth transmitter, none of which are soluble or safe to eat. But, the team predict that this will all change in the next decade.

Current sensors often contain health-damaging metals, but if the scientists can find a biodegradable power supply, the patches could find their way into all kinds of products, monitoring food-freshness in real time.

The secret of CRISPR precision

CRISPR has revolutionised gene editing and is rarely out of the news. Researchers in China have used it to fixed faulty genes in human embryos and a team in London are using the technology to examine the first stages of human development. But just how the system makes genetic edits with such precision hasn't been clear, until now.

This week, a team at Uppsala University have revealed how the it cuts DNA so accurately - it takes its time.

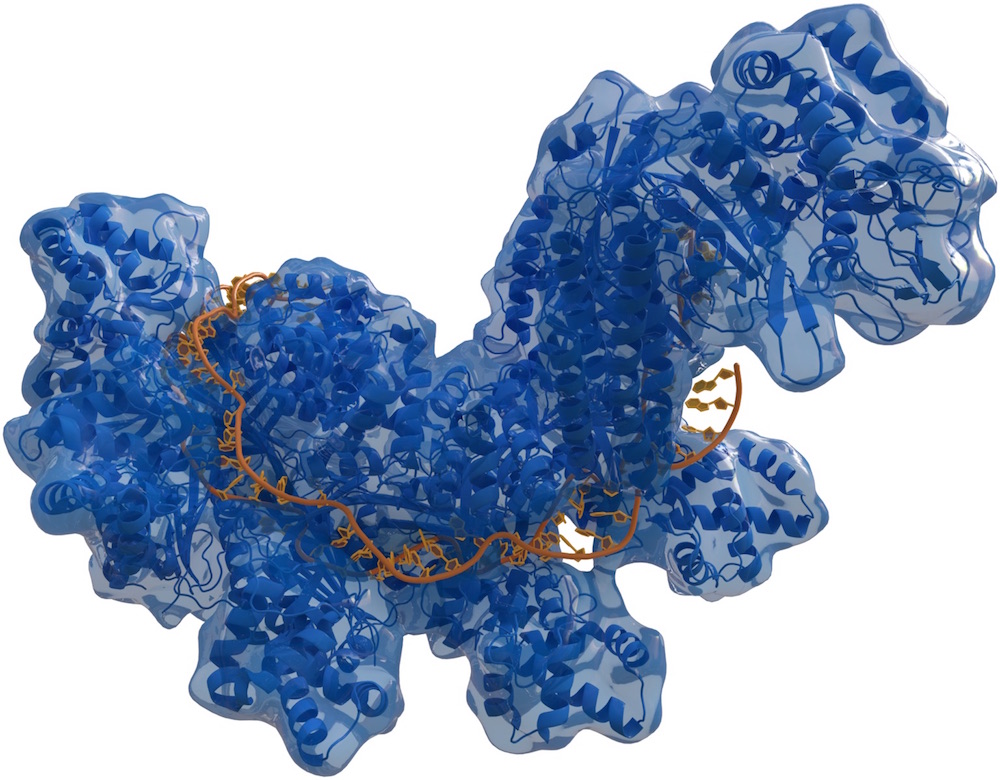

CRISPR is a programmable DNA-editing system that works like a pair of molecular scissors. Scientists guide it to the right place by feeding short stretches of genetic code to a molecule called Cas9, which finds the matching section of DNA before the cut is made.

The latest work has revealed that Cas9 six whole hours to scan a four-million letter genome, examining the outside of the DNA, and then unzipping the helix to compare the sequence inside with the fragment that it’s holding. Each check takes around 30 milliseconds.

Adding more Cas9 molecules can speed the process up, but it increases the risk of side effects. So, armed with this new information, the team hope to be able to build a compromise into the system, reducing the number of times Cas9 unzips the helix and speeding up the process.

"The key is in what are known as the "PAM sequences," which determine where and how often Cas9 opens up the DNA double helix. Molecular scissors that do not need to open the helix as many times to find their target are not only faster but would also reduce the risk of side-effects."

Johan Elf, Uppsala University