Leica and I go way back. My very first digital camera was a Leica, the Digilux 1, a chunky compact unit that was only the German company’s second foray into making a camera without film. Released in 2002, it was developed hand in hand with Panasonic (and was essentially a re-branded and re-styled DMC-LC5).

These were early days for digital photography, back when the main stumbling block was shutter lag. For its time, the Digilux 1 boasted an impressive 4-megapixel sensor (as well as a ‘large 64 MB SD card’ on which to store your pictures) and it’s true, the shutter speed really was quick, with barely a fraction of a second between pushing the button and taking the shot.

The Digilux 1 upset purists, not because it was digital, but because it wasn’t really a true Leica. The partnership with Panasonic sullied the maker’s independence and was deemed as much a departure from the Leica ethos as its foray into making SLRs.

Leica will always be associated with the Rangefinder camera, a design that incorporates a separate viewfinder presenting an offset view of what is being captured by the lens (in its only nod to tradition, the original Digilux 1 also had an optical viewfinder). With a true Rangefinder, you have to focus manually, aligning two slightly offset images of the subject so that it is in perfect focus.

This is hard. When the Rangefinder first appeared in the 1930s, it offered a few advantages; you could set a focus zone so that you could easily and reliably take images of a subject as long as it was within that space. The shutter mechanism was quiet and unobtrusive, and the viewfinder could also show what was going on outside the frame of the image. As a result, the early Leicas became popular cameras amongst reportage and street photographers, being smaller, less formal and more attuned to subtle, rapid shots.

How things have changed. Leica’s last film rangefinder was the M7, introduced in the same year as the Digilux 1. It was followed by the M8 in 2006, the first ever ‘M’ to go digital. Even with an ancient 10-megapixel sensor, the M8 has held its value impressively, especially as the company still supports it. Most importantly, the M8 was compatible with all Leica ‘M’ series lens, a vast spectrum of ultra-high-quality glass that lured many professionals into digital photography for the first time.

The latest iteration is the new M11. We’ve already delved into the camera’s feature set, but getting my hands on one was a chance to experience the Rangefinder difference. Even in lightweight black finish it is still a hefty 800g (the classic silver model is 100g heavier), and there’s a pleasing analogue feel to the dials and rings. That said, there’s a much-improved touchscreen over the M10, with a crisp. clear UI, and the sensor itself is a massive 60-megapixels.

Sign up to the T3 newsletter for smarter living straight to your inbox

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

There’s 64GB of internal storage in addition to an SD card slot (a single RAW shot taken on the M11 wouldn’t fit on the Digilux 1’s memory card). The M11’s shutter action is silky smooth and operates at speeds of up to 1/16000 of a second (with the optional electronic shutter). I tried it with Leica’s 35mm f/1.4 ASPH SUMMILUX-M lens (which costs an additional £4,400 on top of the price of the body), and – let’s be honest here – proceeded to struggle with the Rangefinder ethos.

You need time, effort, and perseverance to get the best from the M11, but once you’ve mastered it, you’ll be taking those classically rich Leica visuals, with pronounced depth of field and crisp focus points.

We’re all photographers these days, but the number of people who actually understand the mechanics of photography itself is dwindling. A smartphone isn’t really a camera, but a massively sophisticated image processor, using algorithms to process light in ways that professional photographers once sweated and strived to achieve. Yet the ability to actually capture light as it is, free from processing, filters, and the actions of multiple sensors, is rarer than ever before. For all its simplicity, the Digilux 1 was essentially a great point-and-shoot, with an excellent lens for the era. My photographs were great.

With the Leica M11, it’s just you, the lens, and the shutter. Not a single one of my fumbling first efforts would be good enough to grace Instagram, let alone T3.com, but the tactile quality of the Leica begged to be taken seriously. Give it time, and this camera could transform the way you see the world.

The Leica M11 is priced at £7,500 (body only). Read more at Leica-Camera.com.

This article is part of The T3 Edit, a collaboration between T3 and Wallpaper* which explores the very best blends of design, craft, and technology. Wallpaper* magazine is the world’s leading authority on contemporary design and The T3 Edit is your essential guide to what’s new and what’s next.

This article is part of The T3 Edit, a collaboration between T3 and Wallpaper* which explores the very best blends of design, craft, and technology. Wallpaper* magazine is the world’s leading authority on contemporary design and The T3 Edit is your essential guide to what’s new and what’s next.

This article is part of The T3 Edit, a collaboration between T3 and Wallpaper* which explores the very best blends of design, craft, and technology. Wallpaper* magazine is the world’s leading authority on contemporary design and The T3 Edit is your essential guide to what’s new and what’s next.

Jonathan Bell is Wallpaper* magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor, a role that encompasses everything from product design to automobiles, architecture, superyachts, and gadgets. He has also written a number of books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. His interests include art, music, and all forms of ephemera. He lives in South London with his family.

-

Nothing's next phone could be a budget powerhouse, thanks to this confirmed hardware detail

Nothing's next phone could be a budget powerhouse, thanks to this confirmed hardware detailOfficial details reveal more about the next phone coming from Nothing

By Chris Hall

-

The biggest mistake you’re making when cooking Easter lamb in an air fryer

The biggest mistake you’re making when cooking Easter lamb in an air fryerCooking Easter lunch in your air fryer? Don’t make this mistake…

By Bethan Girdler-Maslen

-

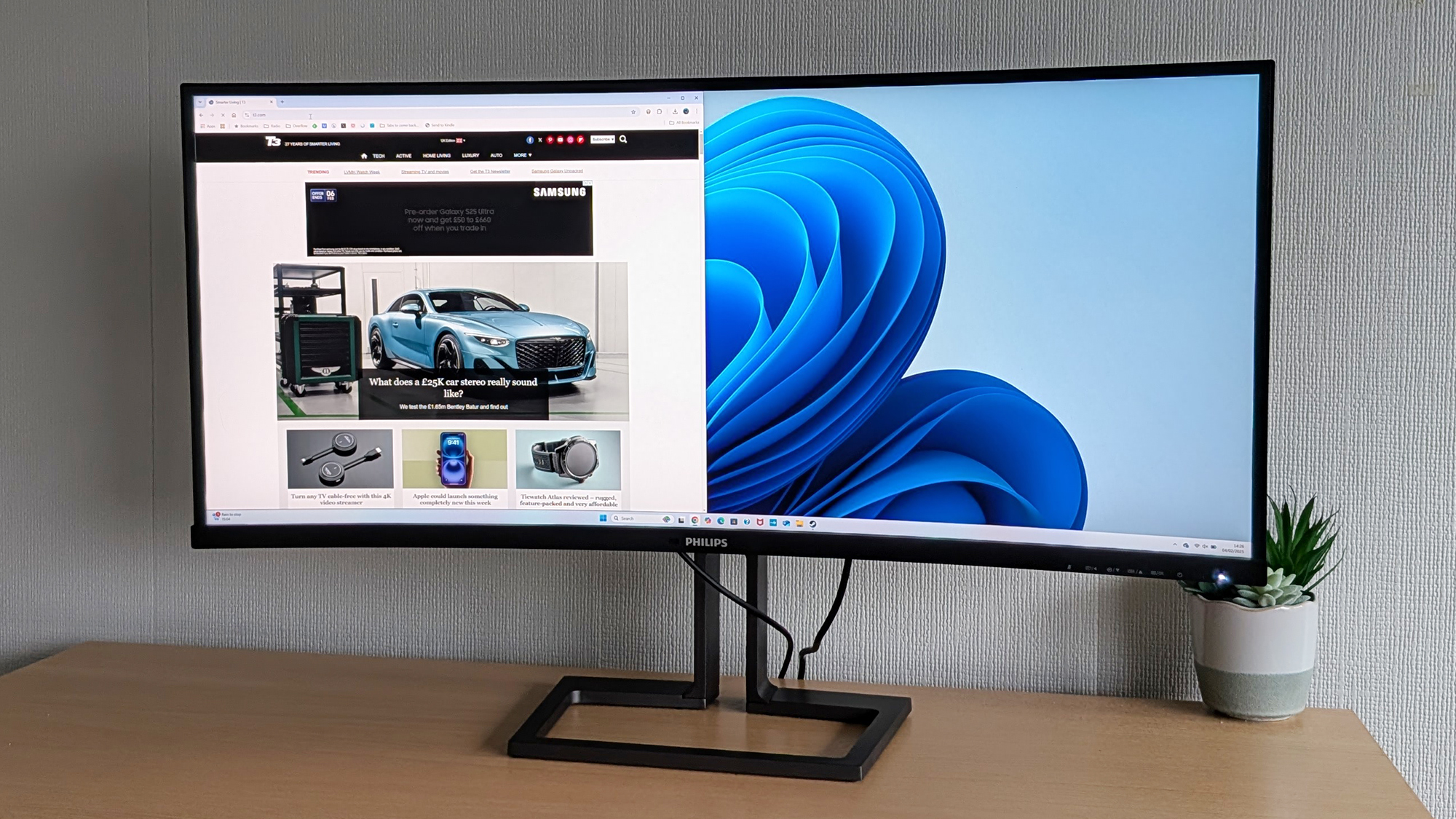

Philips 40B1U6903CH review: a 5k monitor ready to level up your productivity

Philips 40B1U6903CH review: a 5k monitor ready to level up your productivityIt's got the lot for a home office, but gamers won't be convinced

By David Nield

-

Corsair HS80 Max Wireless review: a solid mid-tier gaming headset

Corsair HS80 Max Wireless review: a solid mid-tier gaming headsetA capable audio option for the price you're paying

By David Nield

-

Logitech C920 Pro HD review: a solid and affordable webcam upgrade

Logitech C920 Pro HD review: a solid and affordable webcam upgradeThe Logitech C920 Pro HD has plenty to offer shoppers on a budget

By David Nield

-

Microsoft's 5-star Surface with keyboard is Best Buy's killer deal

Microsoft's 5-star Surface with keyboard is Best Buy's killer dealBest buy it at Best Buy!

By David Nield

-

Sonos' premium soundbar just hit its lowest-ever price in 5-star deal

Sonos' premium soundbar just hit its lowest-ever price in 5-star dealTop-tier sound doesn't have to cost top dollar

By David Nield

-

Huge 75in Sony TV is now cheaper than ever in Amazon's Black Friday sale

Huge 75in Sony TV is now cheaper than ever in Amazon's Black Friday saleYou can now get a top-quality TV for less, with 100s of dollars off this set

By David Nield

-

Improve your Wi-Fi with 5-star Netgear kit – now cheaper than ever

Improve your Wi-Fi with 5-star Netgear kit – now cheaper than everThis is one of the most powerful home Wi-Fi setups you can have – and it has hit a new low price on Amazon

By David Nield

-

Samsung's fan-favorite earbuds are cheaper than ever on Amazon right now

Samsung's fan-favorite earbuds are cheaper than ever on Amazon right nowThe Galaxy Buds FE bring with them a superb listening experience at a low price – and that price just got even lower

By David Nield